october 2021

By Daniel Kaniewski, Contributing Writer

Special Report – Critical Infrastructure

Mitigate the consequences of risks and disruptions that materialize by making disaster resilience a priority in security programs.

A Resilience Framework for the Future

guvendemir / E+ via Getty Images

Terrorist attacks, security incidents and natural disasters can all cause significant impacts to individuals, businesses and governments. Preparing for potential crises and having the capacity to withstand and rapidly recover from them is essential to saving lives and minimizing disruptions. This ability to gird for disruptions and bounce back quickly is at the core of resilience.

At the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), we saw how a focus on resilience could reduce the impacts of disasters. During my tenure at the agency, we prioritized resilience and specifically focused on what I call the “three pillars” of resilience: preparedness, hazard mitigation and insurance.

By making resilience a priority for organizations in any sector, security leaders can reduce disruptions and lessen the consequences from risks that may materialize. This even applies to emerging risks that have recently become very real to many organizations.

Let’s walk through preparedness, hazard mitigation and insurance in turn, and then consider resilience in the context of emerging risks.

Pillar 1: Preparedness

Preparing for potential scenarios that may occur is a cornerstone of both emergency management and business continuity planning. It’s an umbrella term that can include many aspects of readying a government, a community or an organization before disaster strikes.

The first step in a preparedness program is a comprehensive risk assessment. If the risks are not understood by those responsible for addressing them, the value of any of the following actions will be lessened. Investing the effort required to assess and understand an organization’s risks will be time well spent.

Risk-based planning is a second step. Once the risks are understood, plans should be developed to address them. Some will be specific to a particular risk (e.g., tornado, supply chain disruption, or network failure). Others might be more general, such as an evacuation plan for any risk when sheltering in place is not the best option.

Once plans are developed, personnel will need to be trained to execute those plans. This is another essential element of preparedness. Training must be tailored to an individual’s role and a particular risk. For example, a team member in the purchasing department must understand which suppliers are responsible for providing which goods and services following a disaster.

Personnel may also need specialized equipment for these scenarios. For example, security personnel trained to enter contaminated environments will require personal protective equipment.

And finally, personnel should put the plans into action and test them regularly through exercises. These exercises can be of a tabletop or full-scale variety. A tabletop exercise is easier to execute, but only a full-scale exercise (involving actual response actions by personnel) will simulate the conditions that may be encountered in the most realistic way possible.

One must also consider how essential personnel and systems can continue to operate even under stress. This is known as continuity of operations (or continuity of business). The preceding elements of preparedness must be leveraged to ensure that organizations can operate at a reduced capacity and even in alternate locations. During the pandemic, this has meant that a workforce was not simply relocated to a single alternate facility but instead to dozens, hundreds or thousands of employee homes.

Pillar 2: Hazard Mitigation

Hazard mitigation measures aim to reduce the physical impacts of future disasters. Such measures could include:

- Hardening the electrical grid.

- Moving critical facilities outside a flood zone.

- Strengthening the roof of a building.

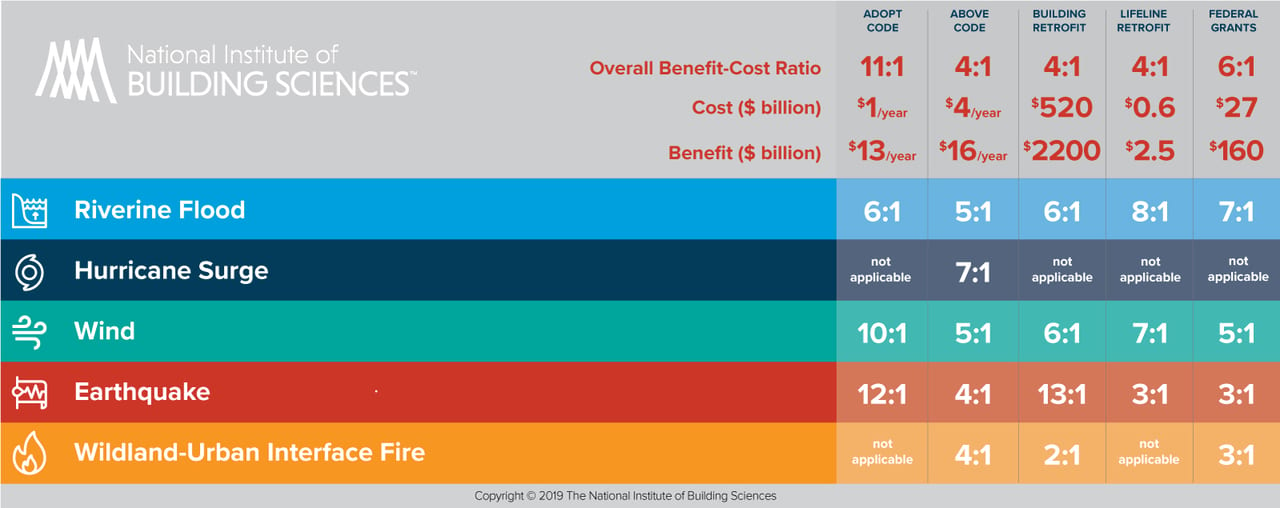

There are tangible benefits from these investments. The National Institute of Building Sciences has shown that on average, for every one dollar invested by the federal government in hazard mitigation projects, six dollars are saved when a disaster occurs.

Image courtesy of the National Institute of Building Sciences

A tabletop exercise is easier to execute, but only a full-scale exercise (involving actual response actions by personnel) will simulate the conditions that may be encountered in the most realistic way possible.

Preparedness is key for any potential risk. If commercial facilities and residential structures are hardened or relocated outside hazard areas, not only will this save money, but it will also save lives. Those occupants will be better protected during a hurricane, flash flood or terrorist attack, and the systems that power homes and businesses, provide water and facilitate commerce will continue to operate even during a disruption.

FEMA recently launched an innovative grant program that aims to fund these worthwhile hazard mitigation projects. The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program provides funding to strengthen infrastructure and communities. FEMA recently announced the $500 million in awards for the first year of the program and plans to fund $1 billion next year. This funding presents an opportunity to reduce future disaster impacts now.

Pillar 3: Insurance

The third pillar of resilience is insurance. Insurance protects individuals, businesses and governments from the financial impacts of disasters. This includes homeowners and renters insurance, insurance for small and large businesses, and insurance products tailored to local, state and national governments’ unique needs.

In addition to these traditional property and casualty insurance lines, two other types of insurance merit further discussion.

Floods are the most common and most costly type of disaster, yet most Americans lack flood insurance. Many believe that they are immune from flooding if they live or work outside a designated flood zone. Not so — the reality is that any home or business can flood. And the effects can be devastating: One inch of water can cause $25,000 in damage.

Pandemics are another risk that have catastrophic financial consequences. As we have seen over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses have been severely impacted by the economic toll of the virus. Pandemics are generally not covered in a business insurance policy, and thus most businesses did not have the benefit of the financial protection they would otherwise rely upon for other types of disasters.

For the future, a public-private partnership that leverages the expertise of the insurance industry and the backing of the federal government is a possible solution to blunt the financial impacts of future pandemics.

Putting it all Together: Cyber Risks

Cybersecurity risks, like pandemics, have transitioned from an emerging risk contemplated as a theoretical possibility to a very real one that has been illustrated by many organizations hit by recent ransomware attacks. But the even graver risk is that of a cyberattack that causes not just financial risks to an organization but far-reaching impacts to an entire city, state or nation. Such an attack could trigger not only widespread economic impacts but physical impacts as well. For that reason, cyber resilience must be imperative to the same degree that natural disaster resilience has recently become a priority (through such programs as the FEMA BRIC grants).

Many states and large cities now have chief information security officers (CISOs) focused on protecting government assets from hackers and other nefarious actors. But just like with other hazards, CISOs need to consider the possibility that an attack will be successful, and that there could be significant physical consequences.

These could be direct physical consequences such as the remote opening of a dam that triggers massive flooding to a community, or indirect consequences such as a power outage leading to traffic deaths (traffic lights) or lack of heat during the winter (similar to the impacts of the Texas power outage earlier this year). And this nexus between cybersecurity and disaster-like physical effects requires cooperation between technologists and emergency managers who may not have previously collaborated.

Thus this new threat requires a focus on resilience, including cyber preparedness, cyber mitigation and cyber insurance.

As the “traditional” disruptions, such as disasters and security incidents, continue to pose risks to public and private organizations, the once-emerging risks of pandemics and cyberattacks are quickly becoming the new normal. Together, we must adapt to this reality and take action now to ensure a more resilient tomorrow.

About the Author

Daniel Kaniewski, Ph.D., was FEMA’s first Deputy Administrator for Resilience and the agency’s second ranking official from 2017-2020. He is now Managing Director, Public Sector at Marsh McLennan and Chair of the Committee on Finance, Insurance and Real Estate at the National Institute of Building Sciences. Image courtesy of Kaniewski

Special Report

Critical Infrastructure

A Resilience Framework for the Future

By Daniel Kaniewski

Special Report

Critical Infrastructure

Cyber-Physical Security in an Interconnected World

By Dr. David Mussington

Special Report

Critical Infrastructure

Protecting the Energy Grid Is a Team Sport

By Scott Aaronson

Special Report

Critical Infrastructure

GridEx: How Exercising Response and Recovery Supports Grid Reliability

By Kate Ledesma

Special Report

Critical Infrastructure

Combatting Security Threats to Our Nation’s Critical Water Infrastructure

By Michael Arcenaux

october 2021 | securitymagazine.com